Upon seeing an artist’s work for the first time, I sometimes think, “They’d be so much better/get more awards/get more recognition/sell more…if they fixed their drawing and proportion errors.”

For the sake of clarity, when I say “drawing” I mean accurately depicting proportions, shapes, and placement of features/objects on a painting or drawing surface. It doesn’t have to be a pencil drawing on paper—it can be a watercolor, a digital painting, an oil painting, whatever. I’m also only talking about realistic art (not abstract).

First a disclaimer: We’re ALL sometimes suffering from some form of Dunning-Kruger Effect. I can be just as delusional as the next person and am often frustrated and struggle with drawing. However, as I have worked to improve my skills over the years, I’ve seen a positive response immediately. In my experience, drawing can be that big of a deal.

“Why doesn’t my artwork get more attention/sales/awards?”

Some artists are discouraged or even baffled about why they don’t sell more paintings or win more art awards. “People just don’t like my style.” “People don’t like the things I paint.” “I just don’t have the opportunities.” “It’s more about who you know.”

I want so desperately to tell them, “No. NO, it’s your drawing. You could be so great—you’ve got so much going for you—but your drawing is holding you back!” I have sometimes hinted around, but it’s hard to get that message across without hurting feelings.

And besides, if they don’t ask me for my opinion, it’s not my place to tell them. (So I guess that’s why I’m rambling about it here!)

“But I have an art degree/I took drawing in college”

And THIS is why it’s hard to bring up the subject of poor drawing skills. You can’t tell some of these artists that there is room for improvement because they assume they’ve already learned all there is to learn.

“I know how to draw. I majored in drawing in college.”

said by someone with poor drawing skills. (It happens all the time!)

The fact is, many college art teachers are likely to give a student a passing grade simply because they show up to class and do all their assignments. But that doesn’t mean that the student was completely proficient in drawing when they completed the class, nor that they learned all there is to learn about drawing. Drawing ability doesn’t stop needing to be developed after Drawing 101 and Drawing 102 have been completed or after someone’s taken a few semesters of figure drawing.

There’s also this whole thing about “deskilling,” where some college art programs deliberately discourage students from refining traditional art skills. Not drawing accurately is almost a badge of honor among some artists and teachers these days. How can any of us trust them to tell us where our skill levels are, when they have no skills themselves?

You can never be harmed by developing more skills

Drawing practice has sometimes been compared to “tedious busywork” and a lot of artists look to find a workaround so they don’t have to bother with it. Maybe their teachers even taught them to use “tools” to trace photos (but this has drawbacks and limitations—as I ramble about on my main blog). But the fact remains that without plenty of drawing practice—drawing from observation—we often lack the knowledge or ability to see when something is “off” in our drawing or painting. The only way to overcome that is to practice, practice, and never stop practicing. More skill and practice can never hurt us, and may make all the difference in our future.

“But I copied the photo exactly!”

A tracing of the outlines in a photo onto our paper or canvas can easily go astray if we haven’t developed the “eye” to catch small subtle changes in shape or contour that throws everything off and makes the final artwork look weird. “But I copied the photo exactly!” doesn’t mean your artwork isn’t looking “weird.” Even if the photo is “weird” too, the viewer accepts the weirdness—because it’s a photo—but will assume that same “weirdness” in your artwork is your fault—not the photo’s.

Sometimes the differences are where the beauty is.

I’m paraphrasing fabulous portrait artist A.J. Alper who wrote a post showing the small, almost imperceptible differences between the reference photo he used and his finished painting (he paints/draws freehand) and said, “This is where the art is.” (Or something similar to that.) He was referring to those almost inevitable differences that happen when you draw or paint freehand. It’s almost impossible to get every detail perfect.

Changes are what makes the painting an original work of art instead of a photocopy. These differences can be part of the charm of the original work. But they shouldn’t be a distortion or weird-looking distraction that is going to be assumed to be unintentional and a sign of a lack of skill or ability.

Artmodelsphoto on tumblr (AKA Posespace.com—they sell reference photos for artists—warning NSFW) posted this “comparison” between their original photo and one of my paintings.

Yeah, there’s definitely a difference between my painting and the reference photo! I assume that artmodelsphoto posted this comparison not to shame me (I don’t think they want to ridicule their customers!) but because the “changes” I put in my painting were not egregious.

I remember working on that painting. I wasn’t trying for a perfect likeness of the model. I only wanted the finished portrait to look like some random handsome “cinematic” man, and not look too wonky and weird, and I hope that I achieved that.

It isn’t always drawing that’s the culprit.

I mean it often is, but it isn’t always. But since drawing accuracy can so easily ruin an otherwise good painting, it’s best to be sure that there are no problems there and rule it out first.

A while ago I knew something was lacking with my painting, especially with my colors. I realized I didn’t have the ability to fix these problems on my own. Some lessons and workshops with the brilliant Adam Clague helped me immensely. (But I still need so much more help! In so many areas! As do we all!)

After studying with Adam for a while, all of a sudden I started selling a lot more paintings. The difference was dramatic. Adam was a blessing straight from God and I am not exaggerating. Lessons with him changed everything.

Enjoy where you are at the moment; don’t be paralyzed by what you may lack

Yeah, I talk about Dunning-Kruger and why we all should be conscious that our skills have room for improvement, and that is true. But with this realization can also come a feeling that everything we’re currently doing sucks. And that’s a horrible feeling to have.

Sure, five or ten years from now, maybe you’ll cringe over something you were proud of today. But be easy on yourself. You’re always in a state of flux, always learning. Besides, not everything you’re doing now is going to suck. People will still enjoy what you do now.

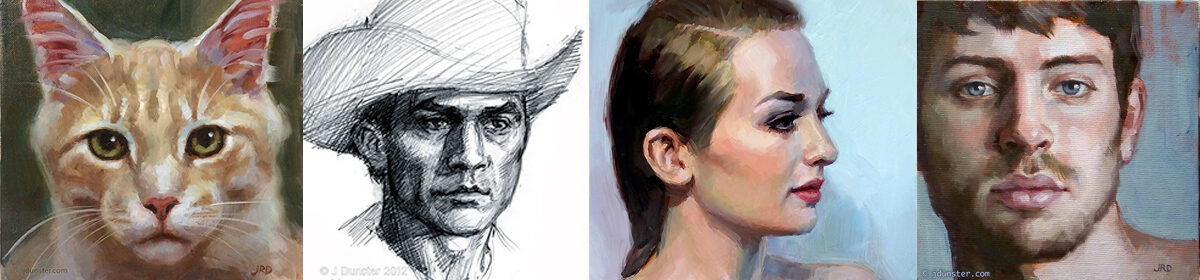

Yeah, “Suspicion,” circa 2012, is not my finest work (the colors are too warm for starters), and it took years to sell, but it SOLD! It is what it is. Someone liked it enough to pay for it, so I console myself with that.

No regrets, “Earnest Cowboy”!

Oh, “Earnest Cowboy,” you hold so many fond memories for me! This painting was done in 2011—2011! and yes, we can point out the flaws, can’t we? But at the same time I still have good feelings about the painting, and the collector who bought it enjoys it, so who am I to regret painting it?

It’s never too late!

Never assume that you don’t need to review some of the skills you first learned in college. But don’t be discouraged or depressed either. There’s always room for improvement in all of us. We’d be suffering from Dunning-Kruger if we assumed otherwise.

Never, never think you’re “too old” or it’s “too late” or “I already studied that.” You can be a veteran artist—you can be a teacher—you can have a lofty art degree, but that doesn’t mean that this is the best you’ll ever be.